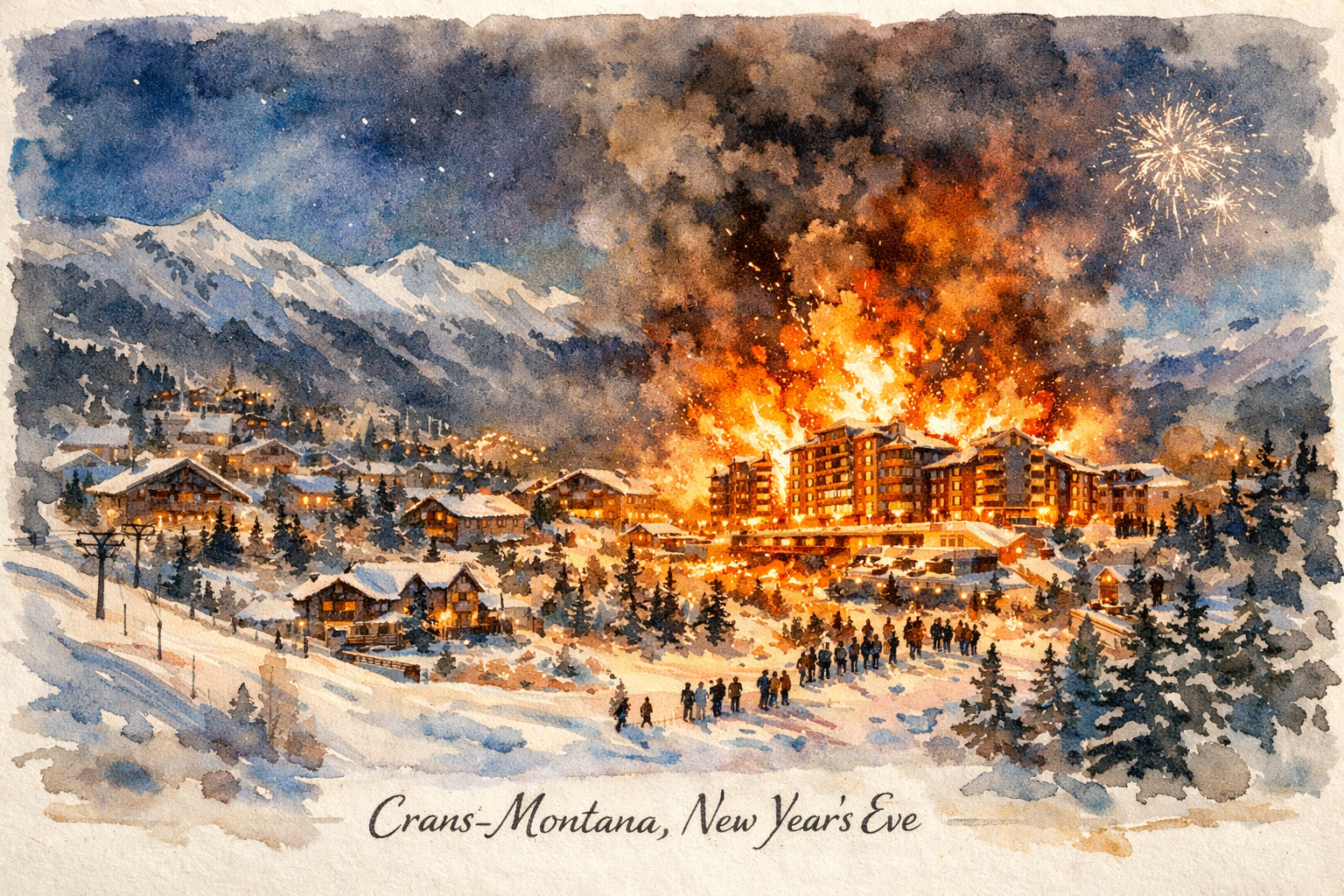

The Night the Mountain Burned

Crans-Montana is the kind of place designed to make you forget gravity—literal and moral. A Swiss ski resort perched neatly above the world, all angles and polish, a place where champagne flutes clink easily because nothing here is meant to feel heavy. Snow absorbs sound. Money smooths edges. Tragedy, when it happens, is supposed to arrive quietly, off-season, preferably somewhere else.

It didn’t.

On New Year’s Eve, in a bar meant for warmth and celebration, fire tore through the room with the kind of speed that only modern spaces—sealed, optimized, decorated for spectacle—allow. Forty-six people died. Many more were injured. And for a few hours, the illusion that this was just another alpine postcard burned away completely.

Early reports point to pyrotechnics. Sparklers. A flourish. Something meant to look good on a phone screen for five seconds. You don’t need to be a fire investigator to understand the poetry of that: a tiny, harmless-looking indulgence that turns catastrophic once oxygen, crowd density, and complacency enter the equation. It’s almost always something small. It always is.

The videos are unbearable, not because they’re especially graphic, but because they’re familiar. Flames climbing faster than panic can organize itself. People hesitating—not out of stupidity, but disbelief. This isn’t supposed to be happening here. The camera shakes. Someone yells a name that won’t be answered. Then the feed cuts out, as if mercy were still an option.

Outside, snow keeps falling. It always does.

Crans-Montana is preparing, even now, for World Cup ski events. That’s how these places survive—by continuing. Logistics don’t pause for grief. Television contracts don’t reschedule themselves out of respect. Crews will clean. Officials will issue statements that include the words deeply saddened. The mountain will look unchanged from a distance, which is the real obscenity of it.

Inside the community, though, nothing is untouched. Families are still searching. Names are still being confirmed. There’s a particular cruelty to disasters in leisure spaces—bars, clubs, resorts—because they strike at moments when people have let their guard down completely. No one goes to a ski resort bar expecting to test their survival instincts. They go to drink too much, laugh loudly, forget the year that just ended.

What happened in Crans-Montana isn’t just about fire safety or pyrotechnics or regulatory failure—though all of that will matter later, in courtrooms and policy briefings. This is about how we’ve engineered joy into something dangerously efficient. How celebration has become performance. How every space is now a stage, and every moment must glitter, even when glitter burns.

I’ve been in bars like that all over the world. Tight rooms. Low ceilings. Decorative wood. Too many people. Too much faith that someone, somewhere, has thought this through already. We trust the setting. We trust the brand. We trust the mountain.

And when it goes wrong, it goes wrong all at once.

The dead will be counted. The injured will heal or won’t. The resort will reopen. Skiers will come. They always do. But somewhere beneath the groomed slopes and the cheerful après-ski playlists, there will be a quiet understanding among those who were there, and those who lost someone: that safety is not a given, even in the most expensive places on earth.

Especially there.

Fire doesn’t care about altitude. Or money. Or tradition. It only needs a spark—and permission. And on a night meant to welcome a new year, it got both.